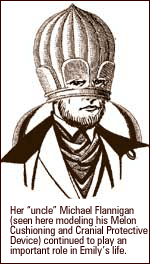

Though known primarily for his prowess as a Victorian inventor, Michael Flannigan had the heart of an adventurer — both qualities inspired his niece, Emily Chesley, in her writing. Flannigan was the only stable adult during Emily’s upbringing and until his untimely and horrific death (testing the prototype of a nostril-stretching and hair-clipping invention) he continued to play a guiding role in her life. You can read more about Flannigan and his work in The Meanderings of the Emily Chesley Reading Circle.

Though known primarily for his prowess as a Victorian inventor, Michael Flannigan had the heart of an adventurer — both qualities inspired his niece, Emily Chesley, in her writing. Flannigan was the only stable adult during Emily’s upbringing and until his untimely and horrific death (testing the prototype of a nostril-stretching and hair-clipping invention) he continued to play a guiding role in her life. You can read more about Flannigan and his work in The Meanderings of the Emily Chesley Reading Circle.

Here are two of his more notorious inventions:

The Lady’s Flatus Inhibitor, circa 1864

The Lady’s Flatus Inhibitor, circa 1864

In 1864 Michael Flannigan and his little clan of Irish hooligans were doing well financially. He was flush from the roaring success of the Whistle-Snap Vitals Binding System (circa 1863) and famous for his Fecal Banishment Apparatus (circa 1860) [1]. On the family front, however, things were not nearly so rosy.

The continual debauchery of his sisters Mary, Hope and Chelsea and their various addictions were a constant drain on his resources, and they gave his other sister Molly terrible gas.

Flannigan well understood the obvious social embarrassment this caused his sister [2], and he saw an opportunity to help her and indeed, all of humanity deal with their intestinal vapours.

By the summer of 1864, Flannigan had created the Lady’s Flatus Inhibitor – a simple device, really, made of cork, a bit of rubber and a small disk of tin. The Inhibitor was designed for easy discreet insertion before a dinner party or an evening of whisk; Flannigan’s intention was that it would prevent the potentially humiliating escape of bodily gases in social contexts. The invention was an immediate hit, and many fine ladies in both Ireland and England were using the Flatus Inhibitor by the beginning of the social season.

Predictably, disaster followed.

At Lady Cecil B. Butrum’s annual Far East Festival the “lentil love” dish was particularly spicy and unfortunately, Hungrup Singh (her Sikh cook) had not prepared the lentils properly. Accordingly, the high level of complex carbohydrates made it difficult – if not impossible – to fully digest the dish. Butrum’s choice of food (and the shoddy workmanship of the sub-contractor that Flannigan had hired to produce the tin disks) would result in what the London Scabrous Times would later dub “The Windy Lake Cross Rip.” [3]

The rough edges of the poorly finished tin were sufficiently sharp to cut through several layers of cloth and projected with enough force, even whalebone. Many ladies present would later say they had a terrible premonition of disaster as they experienced “gaseous abdominal fullness” and “extreme discomfort”. When the music started and the dancing began, the stage was set for disaster.

Nearly 100 Flatus Inhibitors were in use that night, and all but one escaped the confines for which they were designed. [4] Most at high velocities. For the most part, the sound of bustles being blown apart was simply embarrassing, but for the Lady and Lord Jason Foewad, it was tragic. As they ascended to the upstairs parlour in Butrum Manor, it happened: The tension behind Lady Foewad’s Inhibitor finally reached its critical stress point, and it was launched. It was miserable luck that Lord Foewad was two steps below and behind her as the Inhibitor tore through her evening wear at the speed of sound.

The rough edges of the tin nicked Foewad in the carotid artery, and within minutes, he bled to death.

Luckily for Flannigan, the blame for the death could be put squarely on the shoulders of the sub-contractor, so the Windy Lake Cross Rip did not hurt him financially.

But he was – once again – the laughing stock of London: the papers referred to him as “Methane Mike” and “Michael Flatus-again”.

Undaunted by ridicule, financial danger or even the potential death of his customers, he returned to the drawing board, leading him to create the . . .

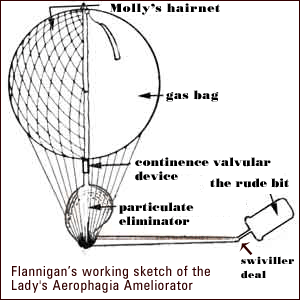

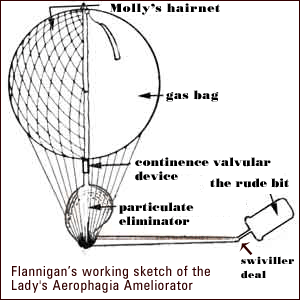

The Lady’s Aerophagia Ameliorator, circa 1865

Clearly the problem with the original design was that it attempted to prevent the escape of such a large and volatile admixture of gases. Instead, why not capture the gases and use them for other things? This was the beginning of his love affair with vaporous fuels that would eventually result in the Library Bosom Affair.

It was also at this time the Fecal Banishment Apparatus was causing in many cases of Glutus Plus Maximus, and instituting the fashion sensation called the bustle. Flannigan had found his solution: The Lady’s Aerophagia Ameliorator.

Starting with the original “plug” design from the Flatus Inhibitor [5], Flannigan added some rubber tubing, attaching it in order to: the “Swiveller Deal”, the “Particulate Eradicator”, “the Continence Valvular Device” and the “Gas Bag”, all of which he patented separately. The prosaically named “Gas Bag” was designed to fit within the confines of a lady’s bustle.

Starting with the original “plug” design from the Flatus Inhibitor [5], Flannigan added some rubber tubing, attaching it in order to: the “Swiveller Deal”, the “Particulate Eradicator”, “the Continence Valvular Device” and the “Gas Bag”, all of which he patented separately. The prosaically named “Gas Bag” was designed to fit within the confines of a lady’s bustle.

Though the memory of The Windy Lake Cross Rip was still fresh in the minds of London Society, its Ladies were keen to try another device to help them with social intestinal indiscretions. [6]

The carefully constructed nature of The Lady’s Aerophagia Ameliorator and the high-cost subcontractors that he employed ensured the success of the invention. It was truly the hit of the 1865 social season, though there were still a few distressing incidents.

The most embarrassing was reported by none other than Horatio Jeeks, the worst alcoholic in London and the writer of the London Barf and Whistle’s gossip column, Addled Chatter:

It seems the nether regions of our Nation’s Peerage are once again under assault from that pernicious Irish inventor, Michael Flannigan. Last night at a piano recital, Lady Felicity Farnshump suffered what can only be described as an intestinal outrage. Apparently, she was using Mr. Flannigan’s “Aerophagia Ameliorator” for several days without respite; the design of the contraption could not withstand the intense pressure of continued use, no doubt made worse by Lady Farnshump’s fondness for cheese and onion sandwiches and the excitement of the music.

In wild counterpoint to the Mozart’s Concerto Number 11, the sound of Lady Farnshump’s Ameliorator giving up the ghost was nothing short of apocalyptic.

In fact, several gentle souls sitting in the row behind her were knocked off their chairs.

In fact, several gentle souls sitting in the row behind her were knocked off their chairs.

Compared with the full-scale (and lethal) disaster of the Inhibitor, the Ameliorator was quite the success, despite with such reports. Even the lower classes found the eliminatory equipment quite useful, though naturally, they found the name awkward and unmanageable. They found a more lyrical way of describing the device: The Flatus Apparatus.

The doxies and nautch girls of the Whitechapel region in particular benefited from the invention. Not only did the Flatus Apparatus keep them from scaring off the customers, they could use the gassy byproduct to light the rooms they used for their assignations. After a while, the harlots who used the device became known as their regulars as the “Sweet FA”.

But this mis-appellation and misuse of the device did not bother Flannigan one bit; for now he was on a holy crusade – to free the human body from the bondage of the bowel! [7]

Notes:

1) Flannigan routinely chose American spellings for his inventions not only because he was always running out of space in advertisements, but because it was one small way in which he could snub the British masters.

2) An interview with the Sultana of Khabstakan nearly ended in disaster because of an ill-timed meal of “Whipple Mix” in 1822 – the incident is reported in the excellent monograph: Flannigan and the Face of Disaster.

3) The Butrum’s had an ancestral home at Windy Lake, and held parties there every year.

4) Lady Bracknell was a legendary tight ass.

5) He patented this as “Device 1245”, but amongst friends and in his sketches, Flannigan always referred to this as “the rude bit”.

6) Though in Joseph “Spungy” Freakinswad’s titembetic masterpiece: “Ode to Odifer”, based on the incident at Windy Lake, he suggests that many ladies simply enjoyed the invasive nature of the device.

7) Though Flannigan was hardly obsessed by the colon. Later in life he enjoyed a brief friendship with Dr. Harvey Kellog (known to many in the health field as the Baron of the Bowel) when they created the Systematic Anti-autointoxication Device, in 1898. Now there was a man who knew his way around a gut.

———–

Thus endeth the “week of Emily Chesley” (which started here.) I hope you’ve enjoyed this taste of the Meanderings. More content will be available in the New Year on the Emily Chesley Reading Circle’s website.

Now, here is humor-blogs.com.

Of all the singing clown acts to grace the stages of Europe and Asia in the first half of the 20th century, none have had the impact that Bingo and Floggie did on the collective unconscious.

Of all the singing clown acts to grace the stages of Europe and Asia in the first half of the 20th century, none have had the impact that Bingo and Floggie did on the collective unconscious. On February 2, it is customary in Canada and the United States to celebrate an annual tradition wherein we allow a chubby burrowing rodent to forecast the weather. This is an important ritual, but not for the reason that many people think.

On February 2, it is customary in Canada and the United States to celebrate an annual tradition wherein we allow a chubby burrowing rodent to forecast the weather. This is an important ritual, but not for the reason that many people think.

To this day crack forces of Amish and Mennonite Grundschweinmörders (Groundhog Killers) spend part of every winter season hunting down resistant forces of the dangerous Tcuckbar groundhog clans. Luckily, evolution has done the rest of the work for us, and the remaining non-sentient species is largely harmless, except to the occasional horse or golfer.

To this day crack forces of Amish and Mennonite Grundschweinmörders (Groundhog Killers) spend part of every winter season hunting down resistant forces of the dangerous Tcuckbar groundhog clans. Luckily, evolution has done the rest of the work for us, and the remaining non-sentient species is largely harmless, except to the occasional horse or golfer. Anaxagoras of Ionia presents “Hot metal, man” (circa 450 BC) –>slide 6

Anaxagoras of Ionia presents “Hot metal, man” (circa 450 BC) –>slide 6

The Lady’s Flatus Inhibitor, circa 1864

The Lady’s Flatus Inhibitor, circa 1864 Starting with the original “plug” design from the Flatus Inhibitor [

Starting with the original “plug” design from the Flatus Inhibitor [ In fact, several gentle souls sitting in the row behind her were knocked off their chairs.

In fact, several gentle souls sitting in the row behind her were knocked off their chairs. FitzWeezepuddle. Near penniless, Michael had a new plan for his dysfunctional family. He’d heard about land being given away in the far western reaches of British North America and he dreamed of making a fresh start. “Surely,” he wrote in the opening entry of a diary dated October 13, 1869, “there must be some demand for locationists. I can only hope and pray.”

FitzWeezepuddle. Near penniless, Michael had a new plan for his dysfunctional family. He’d heard about land being given away in the far western reaches of British North America and he dreamed of making a fresh start. “Surely,” he wrote in the opening entry of a diary dated October 13, 1869, “there must be some demand for locationists. I can only hope and pray.” 1. Scholars are divided on when Emily and her family actually arrived in North America. Whether the event occurred in 1869 or 1870, however, one could only arrive in at Ellis Island, under “Lady Liberty’s fulsome shadow”, after 1884. Also, Ellis Island was not in use until the 1890s. However it is true that nearby on the deck of the Travesty was one Libby Learty, a butcher’s wife from Galway whose six-foot 300-pound frame was said to cast quite a fulsome shadow. This too could be a source of scholarly confusion over accounts of Emily’s arrival in New York City.

1. Scholars are divided on when Emily and her family actually arrived in North America. Whether the event occurred in 1869 or 1870, however, one could only arrive in at Ellis Island, under “Lady Liberty’s fulsome shadow”, after 1884. Also, Ellis Island was not in use until the 1890s. However it is true that nearby on the deck of the Travesty was one Libby Learty, a butcher’s wife from Galway whose six-foot 300-pound frame was said to cast quite a fulsome shadow. This too could be a source of scholarly confusion over accounts of Emily’s arrival in New York City. Friar Parsnip was also the master of the region’s only school, which met every morning after mass for two hours in the 13th century Ennis Friary. It was there that Emily learned to read and love speculative fiction. [3] But while not immersed in the fairy tales told by the Friar or sitting in her uncle’s laboratory while he tinkered, Emily was an unhappy child. Emily was prone at a very early age to outbursts,” as Molly called them; expressed through a twisted combination of violence and creativity, they quite often involved small animals and vaguely satanic rituals. Friar Parsnip tried to control the child, through blandishments of Mary’s love, and warnings that she would drink hellfire. Emily thought of these bribes and threats as mere story telling, and would pat the good-natured Friar on the cheek while she smeared lark’s vomit on the neighbor’s poodle, Yumyum.

Friar Parsnip was also the master of the region’s only school, which met every morning after mass for two hours in the 13th century Ennis Friary. It was there that Emily learned to read and love speculative fiction. [3] But while not immersed in the fairy tales told by the Friar or sitting in her uncle’s laboratory while he tinkered, Emily was an unhappy child. Emily was prone at a very early age to outbursts,” as Molly called them; expressed through a twisted combination of violence and creativity, they quite often involved small animals and vaguely satanic rituals. Friar Parsnip tried to control the child, through blandishments of Mary’s love, and warnings that she would drink hellfire. Emily thought of these bribes and threats as mere story telling, and would pat the good-natured Friar on the cheek while she smeared lark’s vomit on the neighbor’s poodle, Yumyum.